Inman News

Bank failures and potential debt ceiling showdown are wildcards for Federal Reserve policymakers weighing their next move as threat of recession looms

With signs of a recession looming, the Federal Reserve Wednesday approved what some expect will be the final interest rate increase in the Fed’s year-long inflation-fighting campaign.

Having raised the federal funds rate 10 times since March 17, 2022, the Federal Open Market Committee has now brought its target for the benchmark rate to between 5.0 to 5.25 percent — a level last seen just before the Great Recession of 2007-09.

Although bond market investors are betting the Fed will reverse course and begin lowering rates later this year if a recession does materialize, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell would only acknowledge that the Fed could be done hiking rates for now.

While there are many uncertainties that lie ahead — including the impacts of recent bank failures, and a potential impasse over raising the U.S. debt ceiling — future increases will depend on data, Powell said.

“The assessment of the extent to which additional policy firming may be appropriate is going to be an ongoing one, meeting by meeting,” Powell told reporters.

In a statement, members of the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee said they will keep an eye on “labor market conditions, inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and financial and international developments.”

Powell said the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank “does complicate” attempts to gauge the cumulative impacts of tightening so far, which can take some time to affect economic activity and inflation.

“We have a broad understanding of monetary policy,” Powell said. “Credit tightening is a different thing. There is a lot of literature on that. But translating it into rate hikes is uncertain. Let’s say it adds further uncertainty. We will be able to see what’s happening with credit conditions and happening with lending. There is a lot of data on that.”

Of the prospect that Congress won’t raise the debt ceiling in time for the U.S. to avoid defaulting on its obligations, Powell warned that the implications would be dire.

“I would just say I don’t really think we should even be talking about a world in which the U.S. doesn’t pay its bills,” the Fed chair said. “It shouldn’t be a thing. And again I would just say — no one should assume that the Fed can protect the economy and financial system and our reputation from the damage that such an event might inflict.”

Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said in a note to clients that the Fed has already “done more than enough” to fight inflation, and that future data is likely to support reversing course and lowering rates.

“We expect the two rounds of payroll, CPI, PPI and activity data between now and the June meeting to confirm that the economy has weakened markedly and that inflation pressure is receding, so we think the Fed will leave rates on hold,” Shepherdson said. “Note that it is entirely possible that the debt ceiling situation is at crisis point at the time of the June meeting, with markets in turmoil, adding to the case for the Fed not to act. We think the Fed’s next move will be an easing in September or November.”

Futures markets tracked by the CME FedWatch Tool show bond market investors see a 68 percent chance that Fed policymakers make one more 25-basis point hike in June, before reversing course and starting to bring the federal funds rate back down this fall.

On a call with investment analysts Tuesday, Fannie Mae Chief Financial Officer Chryssa Halley said economists at the mortgage giant continue to expect a “modest” recession in the second half of 2023, which could be exacerbated by recent bank failures.

“Bank failures are often part of recessions,” Halley said. “The stress in banking could further tighten bank credit conditions, dampen consumer and business confidence, and lead to reduced consumer spending, business investment, and hiring activity.”

But with many economists also expecting mortgage rates to retreat later this year in anticipation that the Federal Reserve will bring short-term rates back down, Halley thinks housing could be a bright spot in the months to come.

The rapid increase in home sales in response to small rate declines earlier in the first quarter “illustrates our expectation that the pent-up demand in the housing sector will help moderate any future recession,” Halley said.

Mortgage rates don’t always track the Fed’s moves in lockstep, but 10-year Treasurys yields can be a useful indicator of where mortgage rates are headed next since investors have a similar appetite for them. Yields on the 10-year government bonds have declined this week on expectations that the Fed would signal an end to its rate-hike campaign.

While the Fed may be done raising short-term rates, policymakers said they’ll continue to unwind the Fed’s holdings of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and long-term government debt.

The Fed has been letting $35 billion in MBS and $60 billion in Treasurys roll off its balance sheet each month as part of a “quantitative tightening” plan launched last summer to unwind the massive purchases it made to prop up the economy during the pandemic.

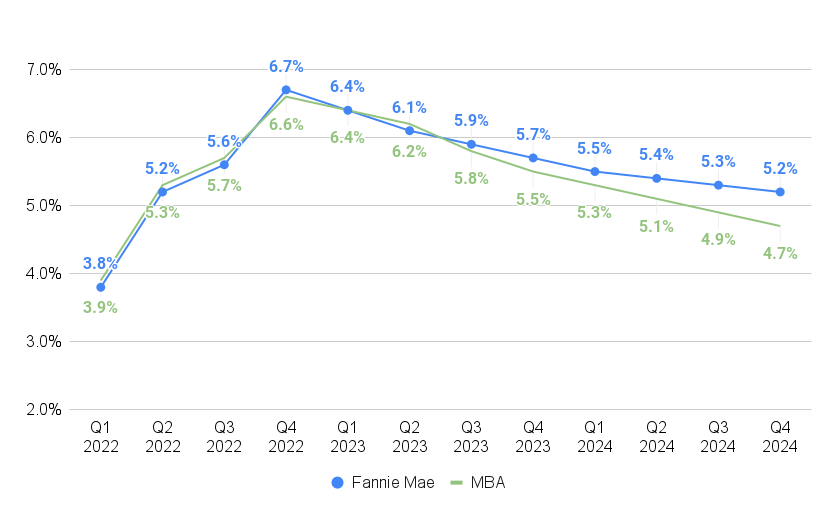

That quantitative tightening is likely to keep mortgage rates from falling too rapidly. But economists at Fannie Mae and the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) do expect mortgage rates will continue to decline from 2022 peaks this year and next.

Mortgage rates expected to ease

Source: Mortgage Bankers Association, Fannie Mae Housing Forecast, April 2023

In an April 17 forecast, MBA economists said they expect rates on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages to average 5.5 percent by the fourth quarter of this year and drop below 5 percent in the third quarter of next year.

Fannie Mae forecasters don’t expect rates to dip below 5 percent while Federal Reserve policymakers are still analyzing what the impact of recent bank failures and tighter lending conditions will be on inflation.