Inman News

A decade ago, the housing market collapsed and Wall Street sputtered. It was the beginning of a decade of deep anxiety that still lingers today. Ten years after crash, the real estate industry ruminates on the dark days and slow rebuild of the housing market.

A decade ago, the housing market collapsed, Wall Street sputtered and banking giant Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. It was the beginning of a decade of a anxiety, economic uncertainty and a slow rebuild that followed. Several real estate professionals shared their stories with Inman on what those days were like in September 2008 and how they were able to move their businesses forward.

What happened?

In the years running up to the crash, lenders eased underwriting standards. Homeowners putting little to no money down for a house became commonplace, and the number of subprime mortgages spiked sharply.

People were simply buying homes that they could not afford in the long term – and really even the short term. Eventually, the market bottomed out: houses went into foreclosure – the year 2009 saw nearly 2.5 million foreclosure starts according to data from Black Knight versus less than 300,000 in 2017 – and prices dropped dramatically putting mortgages that were in good standing underwater.

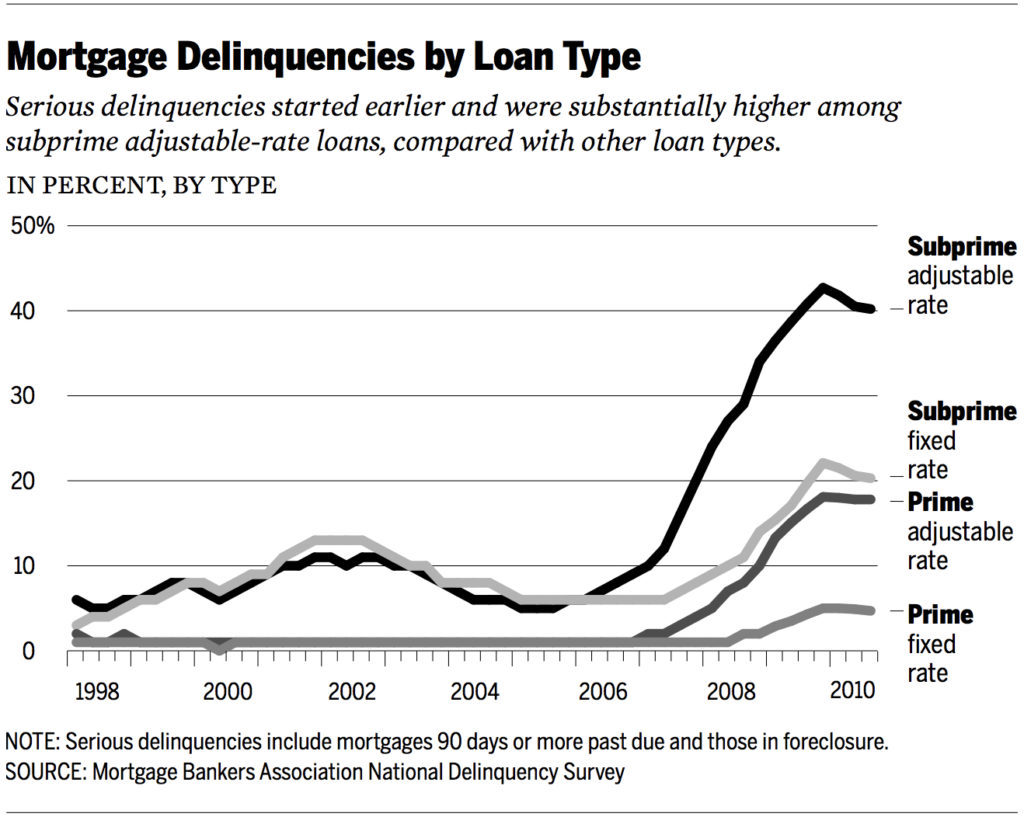

Subprime mortgage went delinquent at a much higher rate than other fixed-rate mortgages when the market crash. (Courtesy U.S. Government Publishing Office)

Lou Barnes, a Colorado mortgage banker and regular Inman contributor, told Inman he believes the blame is often lobbed at the wrong actors when talking about the crash. There’s a lot of misinformation about what exactly happened – which he believes was Wall Street buying and selling bad IOUs.

“The credit bubble was the conscious act of the great Wall Street investment houses and banks,” said Barnes. “The fixed income desks — bonds and IOUs of all kinds — these are the finest credit underwriters of the world. When we began the subprime escapade in 2002 and dropped all sensible criteria from underwriting, every one of the fixed-income desks knew exactly what was happening, what they were doing and got away with it.”

Instead, people often blame the U.S. government and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-sponsored entities (GSE) that purchase mortgages directly from lenders, add to these mortgages a guarantee that the GSEs will pay up if homeowners default, repackage the mortgages into mortgage-backed securities and hold them or sell them to investors.

Peter Wallison, counsel to former Republican Vice President Nelson Rockefeller and a current fellow in financial policy studies at the conservative think-tank American Enterprise Institute, worked on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. He argued the government’s role in the crash in a 2011 story for The Atlantic.

“Before [1992], these two government-sponsored enterprises had been required to buy only mortgages that institutional investors would buy – in other words, prime mortgages –but [Congressman Barney] Frank and others thought these standards made it too difficult for low-income borrowers to buy homes,” Wallison wrote. “The affordable housing law required Fannie and Freddie to meet government quotas when they bought loans from banks and other mortgage originators.”

Wallison argues, in the story, that it was forcing these government-sponsored entities to provide loans to low-income individuals – and therefore relaxing underwriting standards – that ultimately led to GSEs buying subprime and low-quality loans, which in turn, weakened U.S. financial institutions.

Stories from the crash

Ryan Serhant, a real estate agent with Nest Seekers in New York City and star of Bravo’s Million Dollar Listing originally came to New York to pursue acting but decided – while broke and not wanting to move home – that he would pursue real estate as a part-time profession. Maybe he could be a rental agent and help pay his own rent so he wouldn’t have to move back to Colorado, he thought. He started his career in the industry on September 15, 2008, the day Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy.

“I was broke, had no money and had no idea what anything meant or what was happening,” recalled Serhant. “In hindsight, it was the worst, but also the best time for me to get into it, because for a brand new agent, a brand new salesperson — it’s really hard when you get into a market that’s hot because everyone is doing well around you and you’re just learning the ropes.

“When everyone is crashing and burning and you’re just starting off, it’s like, ‘I’m not the only one having a hard time,” Serhant.

Serhant recalls brokers around him getting out of the business left and right, and there he was, sitting in his office – often alone – just trying to figure things out.

“When all of the other agents were getting out of the business, I was the one idiot who stayed in it and kept going through because ignorance is bliss. I didn’t know any better,” said Serhant.

Frederick Warburg Peters, the CEO of Warburg Realty in New York City, has seen a lot of economic turmoil in his nearly four decades in the industry. He was a real estate agent through the housing crash at the end of 1989, when tragedy struck in New York on September 11, 2001, and when the market crashed again in 2008.

“We were all scared, not to put too fine a point on it, scared shitless,” Peters recalled. “I remember that I felt sick to my stomach for six months. I remember that I had two satellite offices that I closed.”

Peters estimated that business was down about 35 percent in the two years surrounding the crash, but he knew it was a time to lead.

“I remember it mainly from my perspective – it was a time when I felt like I really had to show leadership,” said Peters. “We were all scared. And I let it be known that I felt that way too, but I also had to really manifest my confidence that our marketplace was something with enduring appeal.”

Russ Cofano, president and co-founder of Real, was with a traditional top-20 brokerage firm during the recession.

“I remember a day in 2009 when my chief financial officer and I walked into a branch and nobody was there,” recalled Cofano. “And it was a normal Wednesday afternoon. That day has stuck with me.”

How has the market rebounded?

Now, 10 years later, Peters said the reality of the market has certainly rebounded, but the mood hasn’t. He said the period running up to the crash, from about 2002 to 2008, was marked by a sense of ebullience and thinking, “the economy is only going to get better and better.”

“I think the post-recession perspective has been, ‘Okay, we’re going to make this commitment but we’re still nervous,’” said Peters. “[There’s] the sense of anxiety, the sense of something other than prosperity being right around the corner really never left. And that has been a significant factor in the way our marketplace has functioned.”

Serhant echoed those sentiments. He said after September 2008, there was a consumer confidence crisis for good reason, but that crisis still persists today. There’s a little more regulation, but the big banks still control everything and although the stock market is strong, there’s still nervousness and trepidation, Serhant said.

“It’s funny, people have not forgotten [about the crash],” said Serhant. “I kind of thought people would move on – it was 10 years ago – but nothing was really fixed is the consensus that I kind of get.”

A decade later, Barnes argues that the tightening of residential mortgage underwriting as a consequence of the disaster is currently protecting the United States economy.

“Arguably the deepest cycle in boom and recession is the housing market cycle which goes from expansion to overbuilding,” said Barnes. “And simultaneous with overbuilding, mortgage credit has tended to get easier – and the two feed on each other.”

“When the economy begins to roll over, it’s not just that home prices have gotten too high in places, there’s too much inventory,” added Barnes. “And a liquidation cycle begins that often gives the recession a hard bottom. This time around I’m hard-pressed to find any market that’s overbuilt.”

What lessons were learned and how do you prepare for the next crash?

Serhant’s biggest takeaway from the crash – and it applies generally in life – is, “Don’t spend money you haven’t cashed.”

Serhant added that it’s important not to over-leverage yourself, always have a plan B, C, D and E and diversify your business.

“I felt a couple years ago that the market in Manhattan was about to start slowing down … it’s about to be really tough and I started to diversify into multi-family homes in Bushwick and Bed-Stuy [in Brooklyn],” said Serhant. “Every other broker that knew me for doing high-end residential towers and listings in Manhattan and knew me from Million Dollar Listing said ‘What the hell are you doing in that part of Brooklyn doing multi-family homes?”

“I said, you know what, I need to sell as much as possible and I need to diversify what my wheelhouse is and what my skill set is because this market is going to turn,” Serhant added. “And low and behold, over the last couple of years, the market in Manhattan got really tough and my team just got bigger and bigger because we diversified.

Peters guards his company against the next downturn by running his business lean – trying to keep annual costs in line with a conservative way of doing business – and the last crash just reinforced his belief in running lean. Running lean includes evaluating all of the new tech innovations in the industry and deciding what his business needs to implement immediately, what can wait and what it can do without.

“I really try to run my company as rationally as possible,” said Peters. “I really try not to get caught up in any kind of euphoria or any sense that I want to throw money at a lot of unproven stuff.”

But he also knows the industry will always have peaks and valleys and doesn’t believe there’s any way to predict the next crash, especially in a time of such political uncertainty.

“You don’t forecast when it’s going to come,” said Peters. “Nobody knows.”

“We’re in uncharted wildcard territory in terms of our political environment,” Peters added. “Steps are being taken in Washington D.C. that are unprecedented and since they are unprecedented nobody really has much clarity about what the longer term impact of them on the overall economy of the country is going to be.”

Cofano told Inman he’s bullish on brokerage models that leverage technology versus brick-and-mortar brokerages that deliver exceptional agent experiences. He said he understands the culture and human connections are a significant part of the experience, but managing basis points of margin will be critical to profitability – which is hard to do with large physical footprints, he added.

“As we enter the next downturn, that leverage will enable brokerage firms to scale up and down and manage what we all know will be compressed margins, both from less volume and downward pressure on GCI rates,” said Cofano.

In a Facebook comment on Inman Coast to Coast, Sean Carpenter, a real estate agent with Coldwell Banker King Thompson, emphasized the importance of relationships, holding ground, standing strong and having fun.

“[I learned] the importance of building good relationships across all channels of the industry – lenders, title companies, attorneys, inspectors, co-op agents – and leaning on them when needed and lifting them when they need help,” said Carpenter. “In the long run, those who survived and are still here to tell our story about it will hopefully be stronger and ready to face the next market correction/change.”