Inman News

The 9-3 split vote reflects differing views on whether the central bank’s biggest worry is inflation or rising unemployment, with data lagging after the government shutdown

Federal Reserve policymakers voted to cut short-term interest rates for the third time in 2025 as expected on Wednesday, in a 9-3 split vote that reflects differing views on whether the central bank’s biggest worry is inflation or rising unemployment.

While eight Federal Reserve governors joined Chair Jerome Powell in voting to lower the short-term federal funds rate by one quarter of a percentage point, there were three dissenters.

Trump appointee Stephen Miran held out for a more drastic half percentage point rate cut, as he’s done at the last two meetings. Federal Reserve governors Austan Goolsbee and Jeffrey Schmid voted against a rate cut this month, preferring to take a wait-and-see approach before providing the economy with a boost that might reignite inflation.

“Available indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace,” Fed policymakers said in announcing the decision. “Job gains have slowed this year, and the unemployment rate has edged up through September. More recent indicators are consistent with these developments. Inflation has moved up since earlier in the year and remains somewhat elevated.”

At a press conference following the vote, Powell acknowledged that the housing market “faces some really significant challenges,” including supply shortages and the mortgage lock-in effect.

“I don’t know that a 25-basis point decline in the federal funds rate will make much of a difference for people,” he said.

It could be some time before housing market conditions improve, Powell said, suggesting that it would be a mistake to rely solely on the Fed to fix the problem.

“We can raise and lower interest rates, but we really don’t have the tools to address a structural housing shortage,” he said.

In bringing their target for the federal funds rate down to 3.5 to 3.75 percent, Fed policymakers issued projections indicating that they expect core inflation will ease to 2.6 percent next year and 2.1 percent in 2027.

The “dot plot” accompanying the latest Summary of Economic Projections showed Fed policymakers expect to make only one more cut next year and another in 2027.

The three dissenting votes “highlighted just how divided the [Fed] is with respect to future rate cuts,” Mortgage Bankers Association Chief Economist Mike Fratantoni said, in a statement.

“Inflation is well above the Fed’s target, but the job market appears to be softening, even as data to confirm that trend is still delayed due to the recent government shutdown,” Fratantoni said, giving both sides in the debate ammunition.

“Mortgage rates have inched higher over the past week, slowing the pace of refinance applications at a time of year when the purchase market typically slows sharply,” Fratantoni said. “Our forecast is for mortgage rates to stay within a fairly narrow range over the next few years. This forecast becomes more likely as the Fed reaches the end of their cutting cycle next year.”

Powell said near-term risks to inflation “are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside — a challenging situation.”

Fed policymakers have seen “very little data on inflation” since their last meeting in October, he said. The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, showed annual inflation ticked up to 2.8 percent in September — away from the Fed’s goal of 2 percent.

“These readings are higher than earlier in the year, as inflation for goods has picked up, reflecting the effects of tariffs,” Powell said.

But disinflation “appears to be continuing for services,” and most measures of longer-term expectations remain consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent inflation goal, he said.

“There is no risk-free path for policy as we navigate this tension between our employment and inflation goals,” Powell said. “A reasonable-based case is the effects of tariffs on inflation will be relatively short lived, effectively a one-time shift in the price level.”

Forecasters at Pantheon Macroeconomics think unemployment will rise faster than Fed policymakers expect it to, and for “worries about ingrained above-target inflation to melt away next year.”

If that happens, the Fed is likely to cut rates by 1/4 of a percentage point in March, June and September, Pantheon Macroeconomics Chief U.S. Economist Samuel Tombs said in a note to clients.

Upcoming personnel changes on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee “bring the potential for a faster and further decline in rates,” Tombs predicted.

The Fed has now brought its target for the short-term federal funds rate — the rate banks charge each other for overnight loans — down by 1.75 percentage points from a 2024 high of 5.25 to 5.5 percentage points.

But the Fed doesn’t have direct control over mortgage rates, which are determined largely by investor demand for mortgage-backed securities. After the Fed approved three rate cuts totaling a full percentage point at the end of 2024, mortgage rates went up by an equal measure when inflation surged.

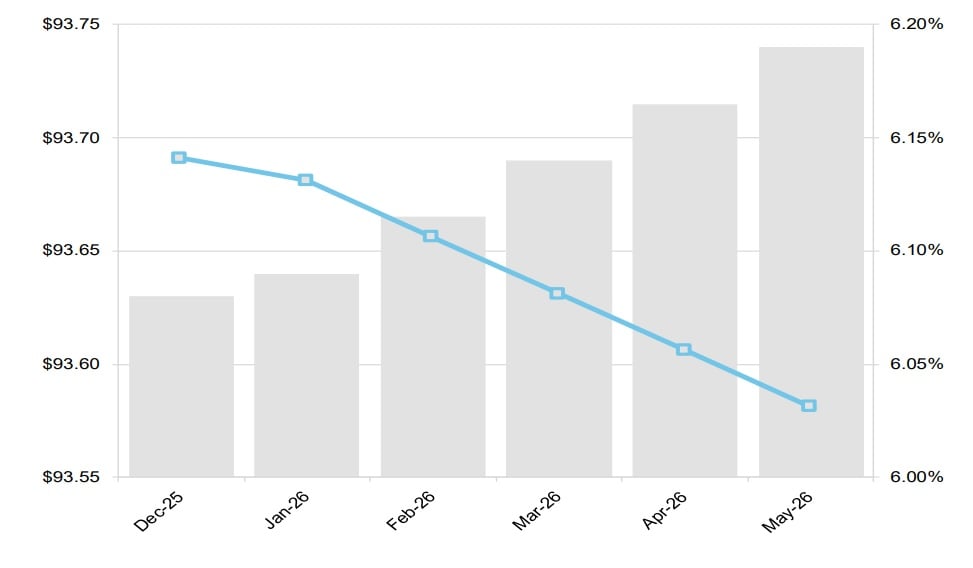

Investors expect mortgage rates to keep falling

Source: ICE Mortgage Monitor, December 2025.

Futures contracts that track the ICE U.S. Conforming 30-year Fixed Index imply that as of Nov. 25, investors were pricing in expectations that mortgage rates will drop into the low 6 percent range next spring.