Today’s extremes won’t last forever, but there’s no silver bullet to end the crisis, and it’s likely shortages in some form will drag on for years.

BY JIM DALRYMPLE II

There’s something really strange happening right now: There are seemingly no homes for sale, and yet the number of actual sales this year is probably going to be up compared to 2020.

How could that be? If there’s a housing shortage, shouldn’t that mean fewer homes will sell?

These questions get at the heart of the current inventory shortage. And more importantly, they hint at how it might, eventually, resolve.

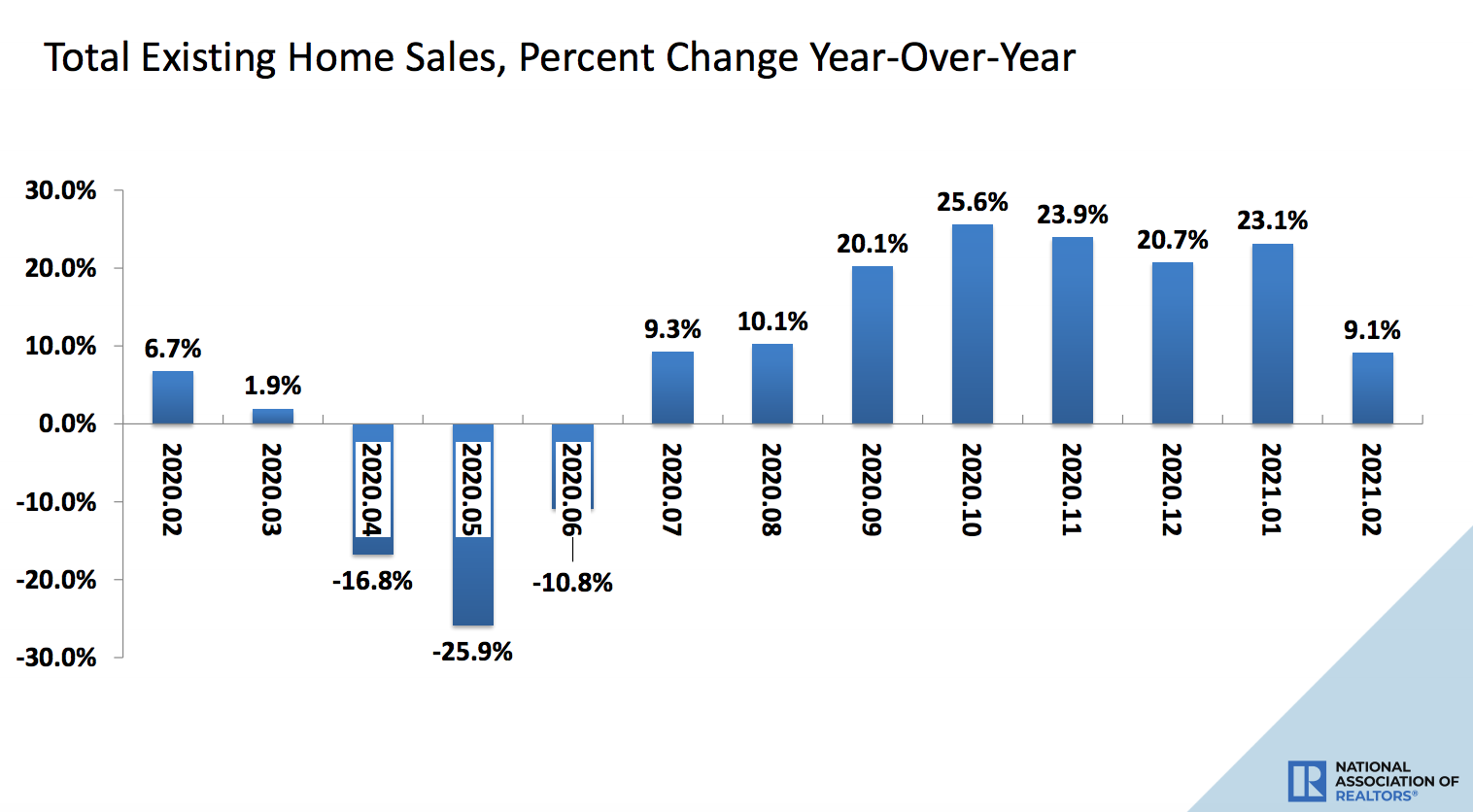

As Inman has reported this week, agents are exhausted, consumers are literally crying after losing bidding wars, and economists are calling the situation unprecedented. On the other hand, data that the National Association of Realtors provided to Inman projects a total of nearly 6.5 million existing home sales in 2021. That’s up significantly from just 5.64 sales in 2020 and 5.34 in 2019.

What these numbers highlight is the fact that “inventory” is a measure of the balance between supply and demand. For example, if the number of homes on the market suddenly doubled, there’d be more supply. But if the number of hopeful buyers quadrupled at the same rate, all those new listings still wouldn’t be enough. There’d be an inventory shortage. And that’s basically what’s going on right now: Demand is outpacing supply.

NAR data shows that despite the shortage, the number of homes sold each month has been up year-over-year for most of the pandemic. Credit: NAR

Why does this matter?

Put simply, it’s because it shows that there are two ways out of this mess: Either supply has to go up to meet high demand, or that demand has to go down. In reality, the solution will probably be some combination of the two, but unfortunately either way the current shortage isn’t likely to dissipate in the immediate future.

Increasing supply

Building more houses

The most obvious way to address an inventory shortage is to simply increase supply. This is the solution that would probably make everyone — agents, consumers, lenders, etc. — most happy because it would mean everyone gets the house they need.

“The only way we can really fix this is we’ve got to build more,” Matthew Gardner, chief economist for Windermere Real Estate, told Inman.

But there are real obstacles to making that happen.

Gardner explained that in some places, such as California or his own home base in the Pacific Northwest, land near job centers is increasingly scarce. That makes development more expensive, and in turn translates to high home prices for consumers — hardly the solution to an affordability crisis.

On top of that, labor costs have skyrocketed. This is partly because, as Inman previously reported, the construction labor pool never fully recovered after the Great Recession. But Gardner also pointed to a deeper issue that could pose challenges: “Labor costs are massive because no one is going to vocational school to become a carpenter or an electrician or a plumber.”

Danielle Hale, chief economist for realtor.com, made a similar point when talking to Inman about the challenges of increasing the supply of new homes. And the challenges in the building sector means new construction tends to focus on a narrow slice of the market.

“Trade workers were increasingly hard to come by at the cost builders were willing to pay,” she explained. “So, builders did an okay job of building at the higher price point. But we weren’t seeing the same thing at other price points.”

Hale further noted that many local governments lately have been “kind of making it difficult to get permitting through” for condos, meaning urban infill is also more difficult to do right now.

And of course the cost of construction materials is way up. This is in part because of pandemic-induced reductions in what manufacturers can make, but there are other factors at play as well. For example, Gardner said the Trump-era tariffs on Canadian lumber are still in place.

Still, even with all of these challenges, it is profitable to build houses right now and Jeff Tucker, a senior economist for Zillow, told Inman that contractors “are catching up.”

But everyone who spoke with Inman for this series said the U.S. has been building too little housing for so long that new construction alone isn’t going to fix the current problem in a reasonable timeframe.

“They’re building very fast,” Tucker said. “But I think it will take several years to meet this excess demand.”

Enticing more sellers to enter the market

The other way to increase supply is to convince more sellers to list their homes. There are many theories as to why this hasn’t happened yet: fears about the pandemic, fears about not finding a new place, wanting to capitalize on future price gains, and even simply contentedness among consumers with their current situation.

Whatever the causes, though, the economists who spoke with Inman said they do expect more sellers to list in the coming months. Tucker pointed to the rollout of vaccines, as well as continued rising prices, and said both things could “bring some sellers off the sidelines.”

He also pointed to what he described as a “silver tsunami” as aging baby boomers leave homeownership.

“That will clearly start to shift the inventory dynamics,” he said.

Still, aside from changes associated with the end of the pandemic, many of these shifts are very long term, and they’ll be happening against a backdrop of more and more millennials hitting homebuyer age.

All of which is to say the supply shortages currently plaguing the U.S. housing market probably won’t be “solved” literally for years.

“I would say, if you’re looking around for a cohort that won’t have quite the same amount of growing pains,” Tucker concluded, “You could look at Gen Z. We could expect them to have a little less fierce competition.”

Reducing demand

Declining interest from pandemic buyers

As has been widely covered, the coronavirus pandemic drove interest from buyers who wanted more space and who wanted to move from pricey places to cheaper ones. For higher income workers, it also in some cases resulted in more time and more money to spend on housing.

But that may be changing.

Dan Smith, a principal at Anvil Real Estate in Orange County, California, told Inman that as the pandemic has improved, would-be real estate consumers in his area have begun to spend less time on home searches.

“We’re already noticing our market here in Orange County beginning to slow slightly,” Smith explained. “We’re noticing more people going on vacation, and they don’t have time to look at houses.”

In other cases, Smith continued, buyers are simply getting a breather from the craziness of the pandemic, and have realized they may not need a new house, or at least may not need it quite as urgently. These changes are slight — multiple offers and bidding wars are still common in Smith’s area — but they do seem to hint at a shift on the horizon.

“Maybe not with prices yet,” Smith said, “but we’ve noticed it impact the market slightly.”

This is an anecdotal example, but it’s certainly possible that the homebuying frenzy the pandemic inspired could lessen as vaccines tamp down the outbreak.

Mortgage rates

Rising mortgage rates may also prove to be a critical factor in reducing demand. And they may have a much more rapid impact than things like building more houses.

According to NAR’s projections, average 30-year fixed interest rates should hit 3 percent in the second quarter of 2021, and then ultimately rise to 3.3 percent by the second quarter of 2022. These are still great rates, but they are higher than the average of 2.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020, and that will translate into higher monthly payments for consumers.

Tucker doesn’t think rates alone will be enough to fundamentally change conditions, but they do seem to be having at least some impact already.

“It’s starting to cool off buyer interest,” he said.

Hale made a similar argument, saying that the soaring prices of the past year can’t last forever.

“Mortgage rates have enabled prices to rise so much without hitting consumers in the pocketbook,” she explained. “But now we’re starting to see mortgage rates turn around and consumers just won’t be able to have the same spending power that they had before.”

Affordability

Whatever happens with interest rates, though, prices can’t rise forever.

“Ultimately there must always be a relationship between incomes and home prices,” Gardner said, adding that affordability has become a serious challenge in the housing market already. “It’s what keeps me up at night.”

So far, apparently, the market hasn’t hit its affordability breaking point. People are still paying more and more for homes. But eventually that growth will have to level out.

“At a certain point you will see affordability become a bigger factor,” Hale said.

The timeline for improvement

All of this is to say that there’s good news and less-than-good news. The good news is that smaller shifts on all of these fronts — construction, new listings, rates, etc. — should mean that the current extremes won’t last forever.

“I don’t think we’ll see a decade of quickly escalating home prices,” Hale said.

Gardner expects prices to continue rising for some time, but thinks appreciation may slow in 2022 or 2023 — a timeline that many agents also mentioned when speaking with Inman for this series.

But the less-than-good news is that there’s no silver bullet and inventory shortages are likely to stick around in some form or another for the foreseeable future.

“We haven’t seen the peak,” Gardner concluded. “This year is going to be a very frustrating year for homebuyers.”

Jim Dalrymple II covers real estate technology. Prior to joining Inman he covered politics, the environment, and general chaos for BuzzFeed News.